When I was a kid I built things from wood and have been handy with tools from a very young age. The forts of summer youth became teen age room additions and these became college furniture projects and then there was my time as a toymaker and then, finally, I found myself a journeyman carpenter in the Pacific Northwest. I never really wanted to be a carpenter as a profession. After college, which instilled many biases in me as to which careers were good and which were intrinsically evil, like journalism, I thought it was a just a simple, honest way to make a buck. I didn’t think of it as a career. I saw it as an extension of my childhood, something I could do without much training and which was enjoyable. No pressed clothes, being outside, the feeling of accomplishment. I slept well after a hard days work. I must say I really enjoyed that period of my life in Port Townsend. I often tell people I didn't pursue carpentry because I jumped at the chance to go to Russia and life put me on other paths, which is true, but there was a certain moment when I realized that carpentry wasn't for me.

I have had several 'dream goals' in my life, many which I am proud to say I have achieved. The carpentry thing was really part of a larger goal I had to build my own house. I have never given up on this goal, but there was an incident that happened that caused me to pause and rethink the whole career calling idea in a general way. It was not a revelatory experience, the kind where the sky opens up and destiny descends and says, "Stop hammering, son. Do this other thing." Looking back, I suppose there were many signs that it was time for a change, but things were not so clear for me at the time. I learned a lot form this experience, not just about what I should or should not do for a living, but about why.

They were terrific mornings, every one of them. The half hour drive down Beaver Valley Road to Port Ludlow was quiet, with very little traffic and stunningly beautiful, especially in the morning. A stop off at a little mom and pop grocery store for a cup of coffee and then soon I was at the site. We were one of several crews putting in foundations or doing subcontracting work for a large tract-home development there. Many of the little crews were from Port Townsend and knew each other and so there was a lot of helping out here and there. We had finished setting the foundation panels, bent and laid the rebar into place and tied everything off before lunch. Our crew foreman, my buddy Eric and I were just waiting for the mud to arrive for pouring when the boss called us to his truck. He told us he wanted us to go down the road with him to help his friend, a fellow contractor, whose crew was putting up frames. There would be no cement today, we had nothing else to do and we were still getting paid, so why not?

The other crew was made up of older guys - they were all in their early forties. Not all big and husky like their foreman, but none of them were journeymen like us, anyway. They had built the floor and frames for two sides of a two story home on a good sized lot somewhat apart from the tract. One framed wall, the one with the peak on it, was easily 20 feet tall. The crew had assembled it horizontally on the open surface of the plywood floor built over the foundation. As I remember, the rules about using 4 x 6 studs for wall frames was already in effect, but I am sure this framed wall was built with 2 x 4's. It didn't really matter, because it was already sheathed with external press board and it was plenty heavy without the 4 x 6's. This is in fact why the guy had called us over to help out. The two teams, a total of about nine or ten guys, were going to lift this hulking wall upright so one guy could run around and slap on braces to hold it up until they tied it in with the other wall they had planned to raise after this one. Why not just build it in place, you ask? Good question. Normally, fames are built off standing structures so they can be built upright. The first wall, however, has to be there to build off. The next question is why didn’t they put up the smaller, more manageable frame first? This is because it was not tall enough to build off of efficiently (with straight, level lines) and because it would be in the way when the crew tried to lift the second wall built in a horizontal position. The central wall has to be a single structure for building integrity – you can’t build part of it and then finish it off when it’s ‘mostly’ up. The last question is why didn’t they hire a crane? Well, cranes are not only expensive, they have to be ordered and scheduled this plays havoc with things like subcontractor deadlines, cost estimate contracts and paid employee downtime. The freedom of a small contracting outfit lies in its ability to circumvent a lot of extra red tape and this is not to be dismissed when thinking about the reason why guys like to do this kind of work, especially educated people. Every guy on our crew, save the foreman, had a college degree. I’m pretty sure it was the same story with the other crew.

The scene was like one of those old time barn raisings you read about, with a bunch of guys in flannel shirts on a bright, late summer day heaving and hoing to get the frame wall up. I was not skeptical at all - I had applied my mind to such problems and realized that experienced guys knew the tricks of the trade and that was why I was here in the first place, to learn. Maybe this method wasn’t official, but I had enough experience of building inspectors to know that ‘official’ ways had no monopoly on good sense and I had no doubt that experience was more practical than the building code, anyway. Besides, no one asked me what I thought. They just told me to stand over there and push when the guy yelled. So after some preliminary hemming and hawing, as carpenters do, we took our places.

The guy yelled and the wall began to go up. I'm sure many people know what a collective rush feels like - the sudden force of gravity that makes strangers into a team. There is a little terror in it, which provides focus. And there is a terrible strength, too, which is every man giving his all so as not to be the guy who didn't do his share, the weak link. There are many places in which a man can hide his failure to his best, even in the physically demanding job of construction, but the collective hoist is not one of them.

We got the wall above our heads and started to 'crawl backwards' with our hands as we shuffled forward with our feet. You don't know what to do, but there is some instinct that gets in you and you follow the lead guy and you know instantly why he is the lead guy. We got the wall at about a 75 degree angle and one guy, who had already nailed a cleat into the floor, put a huge stud up into a window header in the wall, which took some of the burden off and everybody. With our hands still on the wall, we took a moment to get a second breath and better footing for the final push.

And then the cleat gave way.

Every man from both crews was under the wall, which suddenly dropped about a foot and half, leaving everybody hunched with their faces in the wall and their arms cocked back by their ears. The stud that had been used to brace the wall lay useless on the floor. The wall had been nailed into place at the corners and in a few places in the center of the floor runner plate at the base of the frame, and though we all heard the sound of nails groaning and being pulled through wood, the base of the wall held fast to the surface of the floor. Heavy breathing was about all anyone could hear for some seconds. There was grunting and soft cussing, but no one spoke. Everyone was pitched, listening for a word. We just held this massive wall inches from our faces. No window holes had been cut into the frame so there was no escape, really.

The foreman of the other crew holding the wall right next to me just said, "Ok guys, on four." He counted and everybody knew what to do. There was a tremendous heave and the wall went back to where it had been before the cleat popped out. It was like one of those champion weight lifters who goes through a couple of positions before he gets those huge weights over his head. We had miraculously made it to the next stage. But the weight lifter gets to toss the weights down and step back if things go wrong. We did not have this luxury. The pause at this stage seemed eternal. It crossed my mind and must have crossed every man’s mind: we are not going to do this.

I broke down. Something in my arms, something in my back just gave out. My hands never leaving the wall, I looked over to my left at the foreman who was making faces with his eyes closed, straining like a bull. For all I know, he was holding the wall up by himself. I was shaking, partly from the released tension of letting go, but also from shame. It was one of the most awkward moments in my life. I didn't dare leave, though. I hoped at least to be injured with the rest to make up for my, my... what was it? I am not sure even now what happened, if my arms simply lost their physical strength or if something inside me just gave up or what. My mind still gets wound up recalling the event, years later.

Unexpectedly, a little red pickup drove up to the site. It was the contractor’s wife. She hopped out of the car and didn't even take another look at the situation. She ran to us, grabbed a hammer and a few nails from a tool belt lying somewhere and pounded a cleat into the floor faster than you can say Jack Robinson. She grabbed the big stud on the floor and set it in place against the cleat and it held. The wall came down a few inches and everybody let off yells and shouts of relief.

Immediately, the guys jumped down and started slapping brackets onto the sides and more cleats on the floor to hold the giant wall, sagging under its own weight. I stood off a bit and watched them, in shock and shame.

They got the wall into an upright position some minutes later by tying a cable to a heavy truck that was attached the central window frame at the peak of the wall. The truck pulled forward slowly and the crew, levels in hand, shouted when to stop and the quickly hammered everything in place. The second wall was much lighter and the original crew got it up in not time and stabilized the two walls together.

There was some general talk, "That was a close one!" and "Mighty fine of your wife to show up when she did," but on the whole no one seemed to be able to express the feeling of the closeness of God that we had all shared at that moment. Well, everyone except me. I mean, I felt God's presence, too, but I felt like I had lost something. It didn't feel like the victory of a job well done, or the exciting glow of a narrow escape. None of my co-workers ever said anything, which is either a credit to them as human beings or lack of credit to the theory that other men can feel the weight of the man who doesn't pull his own. I helped out on a couple of other homes after that, but no complete projects from beginning to end. The spark of a career working in construction among these men had become very dim.

Of course, construction workers get hurt, they get bad backs and ‘hammer’ elbow and when they get old, they're just old and there isn't any union to take care of them. There are a lot of rough, rude and frankly scary guys in the construction trade as well - stoners and loud redneck radio types who spend their weekends with guns and their paychecks on their vehicles. Guys fresh out of jail or on their way. These guys don't sacrifice anything they don't have to and tend to form a majority of those in the profession. I could give more reasons why a healthy young educated man shouldn't waste his potential in carpentry. The fact is, however, that there are lots of carpenters who are really fine people, heroes, even. Men who may know all that is bad about the construction industry and still choose it out of love of physical work or for creative reasons. For the freedom. Many of them, I found, shared the dream of building their own home one day. Many did. There are the less outspoken men like this foreman who put everything he had into what he did. Something inside me said that if I couldn't put my whole self into this thing the way that guy did, then I was in the wrong line of business. It wasn’t just about carpentry, either. This was a life thing.

So many years later, I find myself an English teacher. I did not imagine this career, either, but I see that it fits me very well, especially here in Russia where it affords a lot of the freedoms that I enjoyed being a carpenter and the propriety of a small business. I don’t usually tell my potential clients in Russia that I was once a carpenter, a ‘stolyar,’ at least not before settling business arrangements. The social connotations of the building trade here are quite different. Carpenters are village people, migrant workers and uneducated. Carpenters drink. Teachers, however, are quite revered. Teaching carries a status similar to that of a doctor and is numbered among the several ‘noble’ professions in Russia which make up for their generally low pay by the status they bring. The distance from carpentry is such that one student, upon learning of my sordid past in the building trade, stopped having lessons.

My wife likes to boast that her husband can cook, which is rare among Russian men. We enjoy having guests and surprising them with new things like Mexican food or some unusual Asian fish dish. Recently I made lasagna and it was quite a hit with out friends, who had never eaten such ‘exotic’ food before. I like to make everything on the table myself, including the drinks and the desserts, if possible. I like the feeling of completeness a successful meal provides. It is a subtle thing, really, because after all, its just food. I think my friends would appreciate less fuss as well, just to be together and talk and eat. Still, challenging myself to make this or that, to find the right ingredients and recipes and to experiment with a technique. I want people to really enjoy themselves and I put as much love ands creativity as I can into whatever I'm making. It is not carpentry, but I put my soul into it. I even went into the final rounds of a job interview as a chef in a Crimean resort. I didn’t get the job, but I felt I cold have done it.

I still have a dream to build my own house, one of the final goals on my shrinking list of things I have told myself I should do in my life. In a twisted way, I hope that cooking and teaching and everything I have done in my life is somehow preparing me for that task. Of course, building your own home is just a more expansive means of providing the right atmosphere for dinner guests, who get to be your family for a while when they sit down at your table. The microcosm of the kitchen is more convenient for a persons creative needs, but one still has macro-cosmic dreams, so to speak.

Creative urges come in cycles, they say. It just might be that God never wanted me to be a carpenter, but that He may let me build a home for myself and my friends all the same.

Greek Style Black Eyed Peas

2 weeks ago

4 comments:

Awesome story. Never heard it before. And I thought you were only making toys up there in the Northwest. A good friend of mine tried to become a carpenter when he was almost 40. That's about the time most guys get out of carpentry. He has many of the same scary stories.

--b

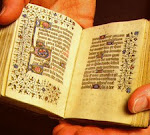

40 is about the age that men who are not in love with what they do stop the hammering. The best carpenters, in my experience, are older men who have learned how to avoid getting hurt and to make better use of the team rather than rely on themselves. I later did carpentry work in Holland as well, with a very talented carpenter. He is now almost 60. We restored buildings from the 'Golden Age'of Dutch commerce, often 300 + years old. It was a pleasure to work with such a skilled man, even if I was mostly hauling debris and holding things.

TJ-

As a sorry sidenote, you remember Gavin (friend of Mary Alen)? He ended up a carpenter. fell off a roof in Chico and died.

a good guy. We never know whehter the wall is going to fall or whether through a miracle or not it holds.

P.S.: you need to post something new. How about a post on how some of us don't live our dreams, become successful, and still our life is the same? Life is shadows and fog, my friend, and you never know when the wall will give.

Sorry to hear about Gavin after all these years. He was also a brave fire fighter. Don't live your dream? I don't have much to say about other people not living their dreams. I feel very lucky have been able to pursue some of mine. Success if largely a matter of definition, I think. I am English teacher. I think I have achieved some measure of success. For others, maybe this isn't enough. If the wall is going to give, well my sapient minnow,should we hide and curse our luck or fall off a roof trying?

Post a Comment